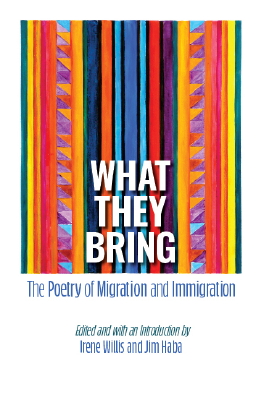

Click Here to Read About and Purchase: What They Bring: The Poetry of Migration and Immigration on IPBooks.net

What They Bring: The Poetry of Migration and Immigration, Edited and with an Introduction by Irene Willis and Jim Haba Reviewed by Roberta George,

Irene Willis, from Massachusetts, is a long-time friend and fellow writer. I’ve followed her career ever since she won Snake Nation Press’s poetry contest in 2005 for her poetry collection called, “At the Fortune Café.” After that, Irene came down to Valdosta to attend our yearly Book Fair at the Turner Arts Center, and we had a great time together: two middle-aged (ha!) women, who through their love of poetry, found new careers and meaning in life. It’s been one of my great joys and an added benefit of being an editor of Snake Nation Press to meet so many wonderful people through their writing, and that’s how I met Irene.

Probably, because of the mismanagement of our country’s borders, and the difficult circumstances surrounding immigration, Irene Willis and another gifted poet, Jim Haba, came up with the idea of collecting poems about immigration and migration called, “What They Bring.” Besides other awards, Haba is well known in the poetry world for his work organizing large poetry events, and in 2011 he received the Paterson Literary Review Award for a Lifetime Service to Poetry.

What can I say about this book, “What They Bring.” I see many poems and many names—W.S. Merwin, Gerald Stern, Sharon Olds, Anne Porter, and W.H. Auden—many I recognize and many I don’t. All I can say is I find it very difficult to read more than a few of these poems at a time. My eyes fill with tears, and my chest hurts and shakes with the feeling that these people have put in their verses.

Till I can regain control, I sit and look out my back patio window, knowing full well how fortunate I am, although I’m not that far removed from the immigrant experiences I’ve just read about. My grandparent’s on my father’s side came from Germany right after the first World War. My German grandmother never stopped saying, “Thank God we escaped the second one,” although she was always preparing for number three. My mother’s people were English in Tennessee, so far back so that there are no immigrant or migration stories in the family, and in spite of their being educators and lawyers, I know from history, that somebody way back then was new to the land and took it. My husband, Noel George’s people are Lebanese. He was third generation in this country but was often called “foreign” and sometimes even “black.” And after he worked all summer, plumbing and coaching, he and his blond cousins could have, as they say, “passed.” Once, in New York, Noel was almost arrested because he resembled so closely an escaped black convict.

And I think of all the immigrants I’ve known, documented and undocumented, and what they have contributed to this country. My German grandparents were undocumented, but their five sons fought for America in World War II in the Air Force, the Army, and the Navy. My husband’s people came through Ellis Island, so I suppose they were documented, and I know their sons, my father-in-law and the Lebanese uncles also fought in World War II. Leona Abood’s father even fought in WWI. The Tuskegee pilots’ parents were probably undocumented, but they certainly fought in World War II. And what of the 700,000 Dreamers, who were just given a temporary stay in America, giving to America. So far, I haven’t heard or read one story of any one of them violating any law.

Still, Irene Willis’ and Jim Haba’s anthology of poetry brings individual stories and experiences to life. Haba’s poem, “Let Them Come,” gives the title to this book: “What They Bring.” And isn’t that what it’s all about? The individual, what he or she remembers: the words, the looks, the detentions, the arrests, and almost all the poems say how universally hard it is to find and make a home in this country. When we are young, especially, what a person in authority, a teacher, a friend, a parent, and what even other children say carries so much weight. We never forget their words.

Probably the most telling poem in the book is Countee Cullen’s poem, “Incident.” Please look it up since it contains probably one of the most hated words in the English language, which I won’t repeat here. But the last stanza says it all: “I saw the whole of Baltimore/ From May until December/ And of all the things that happened there/ That’s all that I remember.”

Irene in her poem, “The Secret at the Back of the Cupboard,” starts her poem with an epigraph and a direction to all writers: “New York City, 1939

The thing you are most afraid to write,

write that.—Nayyirah Waheed”

And so Irene writes the question the other children ask her: “What are you?” and her answer, a person, a human being, a girl, and even an American, is not enough. In another poem her mother keeps the matzoh and the kosher salt in a box in the back of the cupboard hidden away from German eyes and hidden away even from a second husband. Haber writes of “These Angels” and how they come in disguises: “alien, penniless, vagrant, unschooled, unsponsored, undocumented, immigrants among us.”

And I ask myself, “Are we really a Christian nation that believes the story Jesus told of the Good Samaritan?” The Jews and the Samaritans despised each other, and yet Christ is saying we have to take care of the other. Among many insightful, miraculous poems, finally at the end of the book, Irene and Haba select one poem called “Small Kindnesses,” which even brings in the “bless you,” when someone sneezes, a left over from the Bubonic plague. And it’s what we need now, more than ever, the small and large kindnesses that will get us through this recent plague and maybe show us how to take care of each other.

Please order this book from: WWW.IPBooks.net