David Giannini

Good morning, everyone! We last featured David Giannini in 2011, but are welcoming him again now for a very special reason: the gorgeousness of his new book. Yes, the word is accurate, and you’ll soon learn why.

Meanwhile, I do hope you, dear readers, have survived all our recent holidays in the midst of a year like few we have ever known and now come to us fully vaccinated, boosted and masked if you’re not home alone.

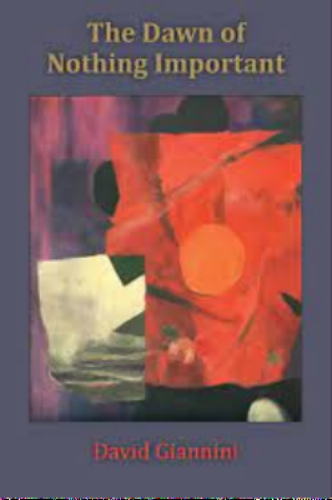

“The Dawn of Nothing Important” (Dos Madres Press, 2022) is so beautiful that I had to stand it up to admire it before beginning to read the poems, which are fully deserving also of anyone’s admiration. It now takes pride of place on my shelves, as it may on yours, unless you choose to display it on a coffee table for visitors to pick up and admire.

Award-winning poet David Giannini has been giving us wonderful poems for many years. But that’s not all he’s done. He has been a gravedigger, a beekeeper, a professor at Williams College, the University of Massachusetts and Berkshire Community College, having begun his teaching career with preschoolers and high school students. Notably, he was the Lead Rehabilitation Counselor for Compass Center, which he co-founded as the first rehabilitation clubhouse for severely and chronically mentally ill adults in the northwest corner of Connecticut. His poems have received a number of Massachusetts Artists Fellowship Awards; the Osa and Lee Mays Award for Poetry; an award for prosepoetry from the Naugatuck Review, a Finalist Award from the Naugatuck Review and a Finalist Award for the James Hearst Poetry Prize of The North American Poetry Review in 2021. One of his books, The Future Only Rattles When You Pick It Up, also published by Dos Madres Press, was nominated for both a Pulitzer Prize and a National Book Award,

–Irene Willis

Poetry Editor

Here now are three poems from David Giannini’s newest book, The Dawn of Nothing Important,” which we have been lauding in the column today:

A Woman in the Asylum on the River

Even in my mother’s womb

I sensed that

I could not escape without help; that there

more meaning entered my desire

to be where I was

coming into focus

under that transducer

and mother’s delusions.

Now, a grown woman,

I am locked in again,

elsewhere, looking out:

you can’t fall out of a river

unless you’re part of the water,

you can’t fall out of the same fluid twice,

even if you’re the spirit of flow

becoming windblown drops on land,

then going deeper through soil to roots.

Trees participate in their standing—

If only I could fly into their green

air—. Indoors, here,

my future’s what’s unstable: rage, meds,

ruthless nourishment. I think filthy sponges

inside me soak up and squeeze out my fears.

The mourning dove is on the sill again—

voice, portable as despair,

I thought you were only a bird.

My captors think I will stay trapped in

this ward, at this barred window,

merely watching, watching

the dove and the river escape.

Time Circle

In Memory of Jonathan Baumbach and Annette Grant

What you had been talking about

how we all know we are

captured by the nabbing clock

the calendar inexorable

Fat chance your deaths took

you whisked by Lethe

to some pavilion of former lives

or parhelion of what you knew not

of light through high crystals

and the sea of herbs

in your garden now your ashes

with the soil the last waves

of our hands bidding rest

with the soil the last waves

in your garden now your ashes

and the sea of herbs

of light through high crystals

or parhelion of what you knew not

to some pavilion of former lives

you whisked by Lethe

Fat chance your deaths took

the calendar inexorable

captured by the nabbing clock

how we all know we are

What you had been talking about.

Thinking of Ludwig Again

As a child he started out standing atop a footstool to reach the piano keys, his punk father beating him for each hesitation or mistake, Ludwig in tears against that drunk.

Decades later, fenced in deafness, he sawed the legs off his piano, to sense the floor vibrate as he played, and later affixed a metal rod to the keyboard, to compose, fingers playing, teeth clenched on that long bar, vibrations conducting in his jaw.

Furled heads of ferns bent over the snail beside an Austrian vineyard, as his publisher hefted a gift of 12 bottles of wine to Beethoven’s deathbed, then heard the composer’s last words in response, “Pity, pity, too late!”

No one knew mercury for syphilis ate and ravaged him beyond silence. Felted wool under hammers, the scroll of his violin in shadow. Outside: fiddleheads, flowers, and the snail a single foot gliding over petals.