I got off the No. 1 southbound local subway train underneath the World Trade Center in Lower Manhattan that bright September day about 8:48 a.m., a minute or so after all Hell slammed into the North Tower 90 or more stories above. At least that’s the time cited by the train’s driver interviewed in the New York Times a week later, though at that time we passengers on that last train to travel under the twin towers knew nothing of what had just happened above.

Pandemonium didn’t begin to break out among us until we were mounting the steps from the platform up to the WTC concourse one floor above. I was about four steps up when those at the top began turning around, some holding briefcases aloft, and pushing back down onto those climbing behind, shouting, “Shooting. Shooting. Go back. Go back.” I turned and jumped back down to the platform, and, after yelling out to the nonplussed driver what was going on so he could radio ahead, I hopped back onto the first subway car. (In his Times interview, the driver, Carlos Johnson, said a passenger had yelled out a warning to him, citing almost exactly the words I had yelled to him: “There’s been a shooting; there’s been a shooting. Someone’s got a gun.” I had no idea then how wrong I was.) But when no shooter appeared after I had stood back on the train for several seconds, my journalistic curiosity and sense of duty overcame my fear, and I knew I had to go and find out what was going on upstairs. So I made a fateful decision to get off the train before its doors closed, sealing my fate, and gingerly mounted the steps again, this time alone, watching for a shooter or any other danger, while a few others were still scampering down around me.

On the ground-level concourse, some people were running in confusion, their footsteps echoing on the new tile floor amid distant shouts, while others still seemed to be walking normally. “Whatever you do, don’t go out there,” said a man whom I asked what the hell was going on. He was pointing through the lobby of the South Tower – a lobby I always walked though on my way to and from work – to Liberty Street, which runs along the south side of the WTC. “It’s a mess,” he added in response to further probing. I pictured bodies on the ground outside on Liberty after the supposed shooting, so I both ran and walked quickly to another exit out onto Liberty Street 80 yards further up. I dashed up some steps and pushed open one of a bank of doors onto the street.

Nothing could have prepared me for the scene outside as I emerged onto Liberty. Everywhere the ground was littered with football-sized dark brown chunks that looked like small asteroids, and millions of sheets of white office paper, some burning. Pieces of metal still occasionally clanged onto the street, and myriad sheets of paper continued to see-saw downward. Vehicles were stopped at odd angles, several on fire, though it took me several seconds to register all this. Searching for the source, I eventually looked up and saw, incredibly, a blaze in the North Tower way up above me, black smoke billowing out, orange flames flickering around high windows, and I assumed a bomb had exploded there. It certainly never occurred to me that a jetliner had crashed into it. The air, which smelled strongly of burning metal and fuel – though I identified the latter only later – was filled with minute floating crystal particles that sparkled in the brilliant sunshine that stunning late-summer morning like tiny snowflakes suspended in the air on a sunny ski slope.

It took only seconds to decide I must at all costs get into the Journal office a few blocks west down Liberty Street if I still could, so I first raced south to get away from the disaster, hoping to avoid any police roadblocks and material falling onto my usual route down Liberty, then cut west through smaller back streets strewn with debris toward the Journal. I looked at the dark brown and black chunks of debris I passed, trying unsuccessfully to identify them. Were they insulation, concrete? If not, what? Later I decided they were seared pieces of building, airplane and everything else I didn’t want to know about. Reaching the West Side Highway at a pedestrian crossing, I dashed across, passing a car stopped on the crossing without any back. The trunk was just sheared off – I guessed by some massive thing that had crashed from above and vanished. The occupants appeared to have fled, though I didn’t hang around to look too closely. A UPS truck emerged from a street opposite me onto the highway, and I gave it a wide berth lest the driver be panicked by what he must have seen. Looking two blocks north along the highway, I saw beside the Liberty Street entrance to a pedestrian bridge that I used every day to cross the highway, the engine compartment of a van engulfed in flames. Later I was told this was in the middle of a large debris field where everything that was thrust through the tower had landed. I used to walk through it every day, and colleagues already at work editing the Asian edition of the Journal, would later tell me of seeing from their 11th floor desks pieces of aircraft rain onto the street there right outside their windows.

I had no idea this had all happened just minutes earlier and how narrowly I had escaped the moment of impact. It would be weeks before I realized how decisions I had made serendipitously that morning at the express subway stop ahead of the local WTC stop probably saved my life. Had I stayed on the express train I had ridden downtown that morning instead of getting off at Chambers Street to wait for the local, I may well have been walking through that very spot on Liberty when tons of pieces of jetliner, people and building from the first impact rained onto the street. I had even passed up a second opportunity to coincide with it all by opting not to take a second express that pulled in and out. One of those two trains would almost certainly have placed me underneath the rain of debris. Instead, I waited for the local, which delivered me directly to the area after the impact.

Once across the West Side Highway, I dashed for the entrance to the Journal building and was amazed I could still get inside, up to the lobby and even into the elevators. I rode up to the ninth floor alone, my heart racing, the seconds ticking by like minutes, then sped to the front-page editors’ windows overlooking the scene I had just walked through. The managing editor, Paul Steiger, and two other editors were already there, looking down upon the unbelievable tableau below, as more emergency vehicles arrived, and looking up at the worsening fires raging though the North Tower. I asked Paul if we would move operations to our South Brunswick campus, near Princeton. He moved several feet away to speak to Jim Pensiero, later credited with immediately writing the memos that moved the Journal to that campus. Then we watched helplessly in horror as what at first appeared to be falling birds, but all too soon became people, began sailing to earth from the tower’s high stories, tumbling slowly in space. I had no idea that further along our building on the same floor and at the point closest to the WTC, foreign editor John Bussey was already at work reporting the scene by phone for CNBC television and that within the hour he would risk his life, remaining there as the nearer tower, the South Tower, collapsed, pelting him with debris, smoke and suffocating ash until somehow amazingly he managed to escape. I first learned he was there when Paul Steiger told me later, before the towers collapsed, that he was concerned about him being still in our building.

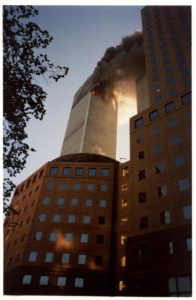

Standing by the windows, I was transfixed by it all when an almighty roar began to fill the air and built to a crashing crescendo with no apparent cause. It sounded as if the girders inside the blazing North Tower were collapsing through its center, but I could see nothing to explain the racket. Only when I looked up at the nearer South Tower, looming high above us, did my eye catch a movement, which immediately billowed into a gigantic orange and black fireball that jetted out the building’s south flank from a second massive explosion. A colleague beside me, Bill Spindle, who had been on the phone to CNBC and who had just told me the blaze in the North Tower had apparently been caused by a light plane, immediately dropped the phone (leaving the journalist at the other end alarmed for him, I later learned). Too close for comfort, the new explosion was all I needed to flee. Still mystified about its cause, I turned, fled my colleagues and ran to the far side of our building to grab my bag, and then to an emergency stairwell as evacuation orders crackled over the emergency speakers. I stopped only to answer a phone ringing on the central news desk where I work. It was a reporter calling for instructions. I told her to use her initiative, and then ran for the stairs.

Inside the large, well-lit stairwell, two stairways intertwined vertically down and around the walls like DNA strands, and people, two by two, were calmly making their way down both. All I could think of was getting out to buy a disposable camera and a notebook to start working, as my old reporting instincts kicked in. But about 10 people below me, a very large woman with a pronged walking stick in each hand was finding the going difficult. Not only that, she was filling the width of the stair, preventing anyone passing. I felt I should do something, so to no one in particular, I bellowed, “There are still many people coming behind,” hoping she would squeeze in to allow people to get past her. But at the next landing, she stopped and stood fully aside, allowing those behind her to scurry past and leaving me feeling more than a little guilty. I couldn’t just leave her there and follow them, so when I got to her, I instead beckoned her to step down ahead of me. She did so, gratefully. I hoped I would still be able to demonstrate that she could make room for those behind her to pass, but her girth was too great, and I reluctantly settled for a painfully slow exit, as did the hundreds behind us. I still ask myself how I could have handled the situation more graciously.

Once outside, I dashed across Southend Avenue to buy a disposable camera and notebook at a supermarket opposite. Yes, it was still open. I even had to hurry the manager along as, incredibly, the salesman in him took over and began to contrast for me the cameras in his range of disposables for me. His assistant, however, was much more attuned to the threat. “I don’t see why we should have to stay here just for a few lousy dollars,” she said. “That thing up there is dangerous.” I quickly agreed and replied, “Maria, just sell me a disposable camera and a notebook, and get the hell out of here.”

With both in hand, I dashed out and began photographing and interviewing on the adjacent plaza by the Hudson where some colleagues stood amid hundreds of evacuees from the WTC as two massive blazes now engulfed the upper stories of both towers high above. Still mystified by the causes of the explosions, I discussed with some colleagues what might have caused especially the second tower to erupt. No one knew. Managing editor Paul Steiger, who was among us, issued instructions to several senior editors for reporting the disaster. Moving away, I called out for eyewitnesses and was shocked when two told me they had seen a jetliner fly into the second tower, and, after triple-checking in disbelief what they were telling me, I immediately asked one to come with me to tell the disbelieving Paul Steiger what she had seen. Surely she meant a light plane, he said. “No,” she replied. “I saw the airline markings, the passenger windows on the jet.” Paul looked ashen as the shock of the words sank in, because for the first time we understood that jetliners, with their fuselages and wings and passengers and fuel, were embedded in the towers above, raising countless grave questions – about the intent of those behind these acts, the enormity of the loss of life, and now the buildings’ stability. Clearly the forest of nearby tall buildings had obscured our view of the second jet’s impact minutes earlier right above us, even though we had seen the fireball that jetted out immediately in its wake. And unlike the rest of the world, we hadn’t seen it all happen live on television.

After about fifteen minutes, which I spent taking photographs while the chilling information about the jetliners sank in, park rangers began advising people to evacuate the plaza. So, with hundreds of other evacuees, I began to trek northward with two colleagues, Lora Western and Robert Rosenthal. Around the yacht basin with its luxury yachts, past the beautiful big glass atrium of the Wintergarden. My two colleagues and I were heading west toward the New Jersey ferry terminal by the Hudson, still no more than 300 yards from the towers, when yet another deafening roar began to emerge from them, reverberating off nearby buildings and off the ground like an almighty avalanche. Suddenly it was apparent that the unbelievable was happening: one of the towers was collapsing. One of my photo images of the North Tower appears to have been snapped at this moment: it is slightly blurred despite being captured on fast 800-ASA film, the only one of 26 images that isn’t crystal clear; beside it appears to be the top of the South Tower, but strangely lower now. However, I only vaguely recall turning back to the towers to take this photo. The shock of the moment was so great that it must have disrupted the memory that was just beginning to embed in my brain. Fearful that the tower would fall toward us, the three of us like all around us began to sprint for our lives, dashing the rest of the way to the river and turning north, splitting up in the process. I had always imagined that, if either of the towers fell, it would do so like a pole falling through an arc hinging from its bases in one direction, so that only things lying in the direction of the fall would be hit. In fact, the steel girders and concrete of the South Tower, just 300 yards away, were crashing straight down to bury themselves in the caverns directly below and in the subway from which I had only an hour earlier emerged and onto the adjacent streets where my colleagues and I had been watching large numbers of emergency vehicles and rescue workers converge. A dense black plume of ash and debris and God knows what else shot out onto the plaza where just four minutes earlier we were standing, and I ran for cover and braced for a jolt of ash and concrete dust and God knows what else that never came, though some of my colleagues did get caught in that cloud. Its toxic contents almost killed one colleague, Rich Regis, from multiple illnesses that developed one after the other in the ensuing weeks and months. Immediately I knew hundreds and perhaps thousands of people had been killed – both trapped occupants and rescue workers – and I tried to focus to pray a silent prayer for them all. It was all I could do. It was all so unreal. I suspect I was in shock and didn’t know it.

After collecting ourselves, all we could do was to resume walking with the throng of evacuees north along the Hudson and away from the scene of the disaster. But as if we weren’t already fearful enough, the anxieties of those all around us slowly snaking north up the West Side Highway leapt at the sound of yet another jet approaching fast. Some began to jostle and scream in panic, and I feared being trampled. But as the jet screamed overhead and we saw that it was a U.S. fighter – the first of several F-16s to reach the scene of the disaster, way too late to intervene – our fear turned to relief. More disturbing news emerged as we passed groups of people on the West Side Highway gathered around car radios reporting the jetliner attack on the Pentagon, rumors of an explosion around the Supreme Court building in Washington, fears of imminent attacks on the Congress building and the White House, and the orders grounding all aircraft.

A half-hour after the South Tower’s collapse, my two colleagues and I were a mile to the north, still trudging up the West Side Highway beside the river, when, with the third and final enormous roar I was to hear that day, the North Tower joined its partner in a deathly collapse earthward, sprouting ash and smoke and debris and people like a gigantic, grotesque Roman candle firework. It was the end of the twin towers, and I knew it was killing hundreds more trapped in the high stories as the upper floors collapsed into the floors below, but somehow nothing seemed to shock any more. Once it stopped happening, leaving massive clouds heaving out from the epicenter, numbed people around us just shook their heads, turned and continued trudging north. My photos even show bicycle riders heading toward the disaster like people enjoying a Sunday promenade in the sun. But the photos also show the numbed faces of hundreds trudging to get away, trying somehow to put all this into some kind of perspective. Months later, I still haven’t completed that process.

As for that last train under the twin towers, the train’s driver, Carlos Johnson, says in his New York Times interview after the attack that when he reached South Ferry, the next and final stop on the line after departing the Cortlandt Street station under the twin towers, his supervisor told him it wasn’t gunfire but just some kind of explosion that had caused almost everyone to leap back onto his train. So he turned the train around and headed back uptown – yes, under the towers one last time. Only when he reached the other end of the line in the Bronx did he learn what had really happened. “That’s when it hit me,” he says. “That’s when it finally dawned on me that I was right in the middle of it. And right then and there, I said a prayer for all those people I saw going up the stairs that day at Cortlandt Street. I hope every one of them made it out.”

Yes, I did, Mr. Johnson, and I thank you for your prayer.

Questions remain: Above all, I continue to ask how I can thank my guardian angel, who, having given me, like Dante, such a frighteningly close glimpse of the Inferno, helped me escape without a scratch. In fact, I shouldn’t have been there at all, and the reason I was drawn there at that hour that one day still causes me to ask deep questions about my life. It was unprecedented for me to be inside the World Trade Center around 8:45 a.m. I always arrived for work at 10 to 10:30 a.m. – the times incidentally at which each of the towers fell. But that Tuesday I had been invited to a small lunch up in midtown at the New York Interfaith Center where Yossi Klein Halevi, a native New York writer who now lives in Israel, where he is the correspondent for New Republic magazine, was to discuss his recently published book “At the Entrance of the Garden of Eden” – the chronicle of a two-year exploration by a religious Jew of the devotional life of contemplative Christians, Muslims and Jews in the Holy Land in the hope that these mystics might – if they could work together – hold the key to resolving the deep religious and cultural conflicts rifting the Middle East. The interfaith center, heavily involved at the United Nations, works to increase understanding among different faiths in our troubled world. So I had decided to arrive at work early to test whether I could, for the very first time, actually take such a lunch break and still get all my work done by deadline. Needless to say, I never made it to Yossi’s lunch talk, though I did later meet Yossi when he told me he next was visiting New York. We hugged and he inscribed my copy of his book, “To Michael – Fellow seeker, fellow journalist, fellow Sept. 11 survivor; in anticipation of our new friendship – God be with you – Yossi.” But, given what we now know of the motives for the attack, what sense am I to make sense of this incredible irony?

Months later, the Journal is still produced from a back-up newsroom an hour from New York near Princeton, New Jersey, to which we evacuated Sept. 11. A return to the World Financial Center isn’t anticipated before midyear. But through the whole ordeal, despite the Journal’s proximity to Ground Zero, the paper has published as usual without a break, seemingly as though nothing had changed.

Yet everything has changed. Little will ever be the same.

– Michael Connolly, early 2002 (written through from earlier versions)